Books in Spanish That Strengthened the Bond Between My Child and My Language

The original plan was to read children’s books in their original language, taking advantage of the bilingualism (Spanish/English) I envisioned for my son. Finding books in English would not be a problem. Accessing books originally written in Spanish would be trickier because we were living in the U.S., but since I live in a border town, I was hopeful.

I located a section with books in Spanish at the local branch of a large retail bookseller (ten years ago, small independent bookstores were still a few years away in El Paso, unfortunately). The shelves had books of all sizes and for different stages of reading. This section was tucked away, next to cookbooks, novels, and the rest of their inventory in Spanish, far away from the children’s section. I tried, repeatedly, to convince the managers to move children’s books to the children’s section, but they wanted to have languages separated. My differences of opinion did not stop me from going — after all, they carried titles in Spanish, and that’s what I needed.

As with many intentions parents have, there were unforeseen circumstances that changed the original plan. Looking at bilingual editions and books in Spanish, I repeatedly encounter oversimplified or stereotypical portrayals of Latine children as presented by the book market for children in the U.S. Even on bookstore shelves with the good intention of bringing diversity to their catalog, their selection would cater to questionable preconceived notions of what it meant to be Latine. Sometimes there was diversity in the last names of the authors, but the diversity of their stories was insufficient in offering more than one version of the Latine culture.

My original plan had to change because, more than anything, what I wanted my child to see in my language was possibility. I needed my son to see Latine kids represented beyond narrow and flattened narratives, which was difficult because the divisive politics of the times when he was growing up were all around us, swallowing cultural identities whole.

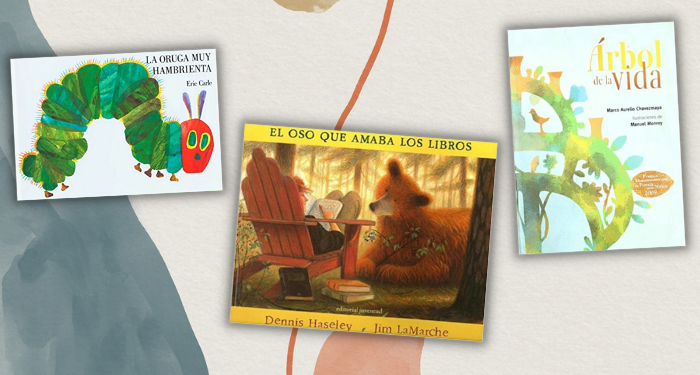

One of the solutions arrived unexpectedly when I was working on a community project with a woman who was a librarian and literary promoter. She gifted us copies of Eric Carle’s The Very Busy Spider and The Very Hungry Caterpillar – in Spanish! (La araña muy ocupada and La oruga muy hambrienta) These translations were a game-changer. I had been so invested in finding ways to bring books from outside the U.S. that, had they not been gifts, getting books in translation for my son would have felt like a kind of betrayal to my language. But I understood then that translators were allies in my quest. The difference between these books and the ones commissioned to address a growing market for children’s literature in Spanish was that the spider was not a Mexican spider; she was just a spider. My son learned to read with the very hungry caterpillar, counting in Spanish the oranges, strawberries, and apples. He built a connection with books before they asked him to make assessments about who he was – those questions would come later, in their own time.

When I felt he had reached the stage where he would appreciate these subjects, I did want my son to know where part of his family came from, and I wanted him to have context for our world. I had to be patient and order books from international distributors. Sometimes, the books would take a long time to arrive, and I would worry if by the time they did my son would already be an adult, but then I figured even an adult needs context for the world of their families.

Patience and research brought us Mi papá es un tlacuilo by Sandra Siemens. The protagonist of this story is a boy living in pre-Hispanic times in Mexico who learns about the art of the tlacuilos from his father and spirit guides. I loved finding books like this one because they would allow me to reconnect with the history of my country. With these books, I also learned alongside my son information I had not been exposed to when I was a child, even though I grew up in Mexico. Mi papá es un tlacuilo taught us about the tlacuilos, who were the artists in charge of painting murals in the temples of Tenochtitlán.

We also read Los antepasados para niños by Sandra García Dávila. This book also took us to México before the arrival of the Spaniards, bringing us closer to monuments, calendars, everyday life, and traditions from centuries ago. We read Un misterio en el laberinto by Italo Calvino; Las lágrimas de Naraguya by Catalina Gonzalez Vilar; Baak, a Mayan story by Judy Goldman with illustrations by Fabricio Vanden Broeck; and one of our favorite books, El coyote tonto by Felipe Garrido.

As someone who learned a second language, I knew if I wanted my son to have strong foundations for speaking, reading, and writing Spanish, Spanish would have to offer him a place he wanted to spend time in, a place to inhabit, and where he could have fun. In the early years of reading with my son, poetry and riddles were crucial to achieving familiarization with Spanish. They gave us opportunities to appreciate the playfulness of words and their sound. We read many times Árbol de la vida by Marco Aurelio Chavezmaya, with illustrations by Manuel Monroy. It is a beautiful collection of poems about the things that surround a child’s life, butterflies, their grandfather, their mother, birds, school, rain, and hummingbirds. We spent a lot of time playing with José Emilio Pacheco’s translation of Monika Beisner’s Book of Riddles, El libro de las adivinanzas.

Another book we love to read together is Cuentos Populares Mexicanos, gathered and re-written by Fabio Morábito. This collection includes 150 short stories and original illustrations by various artists. Rooted in oral tradition, the collection covers stories from different regions of Mexico, from Sonora to Chiapas, from the Tarahumaras to the Chontales. It is a presentation of the different ways to appreciate the world, natural and human, from the richness of the different groups that have lived in these territories. This book is a permanent object in our living room and one we like to open randomly when we feel like traveling to fantastic places.

Good luck brought us a translation by Christiane Reyes of A Story for the Bear, El oso que amaba los libros. This was one of the books we read over and over, imagining the friendly bear who sat in a cave in the forest reading books. Maybe he was reading some of the same books we were reading, we would say. Another bear we loved was in a book by Julio Cortázar, Discurso del oso, with illustrations by Emilio Urberuaga. This is the story of a bear who lives in the pipes of a building where he witnesses the interesting and sometimes lonely lives of the humans who inhabit the building.

One day, I found the series Mondragó by Ana Galán and illustrated by Pablo Pino. These were some of the first books my son read by himself in Spanish. They were a great find because the Spanish they used was from Spain, which offered the opportunity to discuss the many shapes, tones, and textures a language can have.

The book market in Spanish has grown greatly in the U.S. in recent years, which makes me envious and happy for parents with young children. There are even book clubs in Spanish from projects like Lineas del Sur that bring books into the U.S. from small independent presses in Latin America. At large retail book stores, books for children in languages other than English may still be away from small chairs and tables, in boring hallways without colorful carpets, but these sections are growing.

As I pulled one book after another from our bookshelves to write this article, I realized that in many ways, we were very lucky to be away from my country. I can’t help but wonder how much would I have settled for the books available to me in Mexico if I had not been watchful of how my culture was being represented by others. Being in the U.S. pushed me to reach out to different pieces of Latin America, different versions of a language, and different imaginations to bring to my son’s bookshelves international communities that would complement and help shape his vision of the world.

!doctype>