How Wisconsin Became the GOP’s Laboratory for Dismantling Democracy

In his snug campaign office in suburban Milwaukee, located in a shopping plaza next to a dentist and an acupuncturist, Wisconsin Gov. Tony Evers scans the brightly colored maps that hang on the walls. They depict the tortuously shaped legislative districts drawn in a state now regarded as one of the most gerrymandered in the nation. “Who in their right minds could’ve made them up?” Evers asks.

The answer: Republicans in the state legislature. Evers saw firsthand the impact of GOP control of the redistricting process when he ran for governor in 2018. That year, Democrats swept all five statewide races and won 53 percent of votes cast for the state assembly, but the party retained just 36 percent of seats in the chamber. “It’s real simple,” Evers says, after eating a Five Guys burger for lunch. “All the statewide elected officials are Democrats… But then you go into the legislature and it’s almost two-thirds Republicans. There’s something wrong with that picture.”

Evers, 70, is about as low-key as his campaign office—a mild-mannered, grandfatherly figure who could not be more old-school Wisconsin. He likes polka, the card game euchre, and Egg McMuffin’s, despite being “so irritated at McDonald’s” for no longer offering breakfast after 10:30 a.m. After serving as the state’s school superintendent for nearly a decade, he ran against Scott Walker on bread-and-butter issues; his signature phrase on the campaign trail was “fix the damn roads.” But in his re-election campaign this year, he faces a more existential battle to preserve what’s left of democracy in the state.

If the redistricting maps drawn in secret by Republican staffers and passed by the GOP-controlled legislature in 2011 were unfair, the new maps adopted by Republicans in 2021, over Evers’ objections, are even more one-sided. As a result, the number of GOP-leaning seats in the state assembly has increased from 61 to 63 out of 99 and from 21 to 23 out of 33 seats in the state senate. Democrats would have to win the statewide vote by 12 points just to get to 50 seats in the assembly, according to calculations by Marquette University Law School research fellow John Johnson, while Republicans could garner a majority with just 44 percent of votes.

Governor Tony Evers with State Representative Robyn Vining at a meet and greet event at a local business, Tosa Block Party, in Wauwatosa.

Lianne Milton

Republicans are spending millions of dollars to replace Evers with Tim Michels, a Trump-endorsed construction executive who owns a $17 million home in Connecticut. He says that “President Trump probably would be president right now if we had election integrity,” and has pledged to consider signing a bill to decertify the 2020 election. Polls show the governor’s race to be a dead heat.

But the GOP also has a backup plan in case Evers holds on: If the party can pick up just one more seat in the senate and five in the assembly, it will have a two-thirds supermajority in the legislature. That would give them unfettered authority to override Evers’ vetoes and implement an extreme and unpopular agenda on issues ranging from guns to education to abortion. It could even give them the ability to overturn the results of elections. “If Republicans get supermajorities in the state legislature,” says Wisconsin Democratic Party chair Ben Wikler, “it’s a threat to the foundations of American democracy.” That result would bring to fruition a blueprint to fully strip Evers of his power that began the moment he was elected six years ago.

Wisconsin has long had an outsized role in shaping the trajectory of American politics. For many years it had a proud progressive history and paved the way for landmark policies like Social Security, unemployment insurance, and collective bargaining rights for unions on a national level. Teddy Roosevelt called Wisconsin “a laboratory for wise experimental legislation aiming to secure the social and political betterment of the people as a whole.”

But when Walker and the Republican legislature took over the state in 2011, they launched a counter-revolution that methodically undermined democracy and rolled back Democratic power while consolidating their authority over all levels of state government. “If we can do it in Wisconsin, it can be done anywhere,” Walker wrote.

Walker’s signature priority—stripping public sector unions of collective bargaining rights —was aimed at defunding and demobilizing one of the top allies of the Democratic Party and progressive causes. National Republicans quickly saw the measure, known as Act 10, as a model to emulate. “If Act 10 is enacted in a dozen more states, the modern Democratic Party will cease to be a competitive power in American politics,” wrote the influential conservative strategist Grover Norquist, president of Americans for Tax Reform. “It’s that big a deal.” (Union membership in Wisconsin is now half of what it was a decade ago.)

The legislature followed Act 10 with more sweeping measures to entrench the GOP’s power, such as a series of laws that made it harder to vote, which one GOP senator allegedly admitted privately was aimed at depressing turnout in “neighborhoods around Milwaukee and the college campuses around the state,” according to the testimony of a former GOP legislative aide. Republicans also dismantled the state’s strict limits on political donations to give the wealthy corporate interests that bankrolled the GOP far more sway over state politics. These efforts were replicated by Republicans in other states and helped define the priorities of the national GOP. “What we’ve seen over and over is that Republicans use Wisconsin as a Petri dish, as a testing ground, for anti-democracy innovations that they then export nationwide,” says Wikler. Now 2022 could mark the triumph of the Wisconsin GOP’s anti-democratic experiment.

As the Republican Party turns against democracy, with a majority of GOP nominees for Congress and key statewide offices having denied or questioned the results of the last election, Republicans in Wisconsin are again on the cutting edge of attacking free and fair elections. Trump has made Wisconsin the focal point of his obsession to decertify the 2020 election, nearly three-quarters of Republicans in the legislature acted to discredit or overturn the results, and candidates who’ve questioned the outcome of the last election are running for governor, attorney general, and secretary of state. The GOP appears eager to wrest control away from the bipartisan commission that supervises elections in the state and give that power to the ultra-gerrymandered legislature, which could then choose the state’s presidential electors instead of the voters.

That nightmare scenario, which Trump haphazardly tried to pull off in 2020, is now dangerously close to becoming a reality. Wisconsin Republicans are laying the groundwork to potentially overthrow the election in 2024 through more sophisticated and ostensibly legal means. “If we’re talking about things that are anti-democratic and concerns about the integrity of our elections,” says state Rep. Greta Neubauer, the Democratic leader in the assembly, “the threat that the legislature would decide who won the presidency rather than the voters should be at the top of the list.”

When Democrats finally defeated Walker in 2018, it was supposed to usher in a new era in Wisconsin politics. “The voters spoke,” Evers declared at a victory party in Madison. “A change is coming.”

But Robin Vos, the GOP leader in the assembly, and his then-Senate counterpart, Scott Fitzgerald, had other ideas. Less than a month after the election, the legislature convened an unprecedented lame-duck session to strip the incoming governor of key administrative and appointment powers and also to suppress Democratic turnout in urban areas by shortening the early voting period. The Republican-dominated legislature went on to refuse to confirm members of Evers’ cabinet, block his appointments to key state agencies, and cut his popular budget priorities, including money for health care, schools, and roads.

The lame-duck session showed how much power the legislature could exercise without public support—the very type of power grab Republicans are now hoping to replicate across the country. In hindsight, the soft coup in Wisconsin seems like a practice run for the full-on coup attempted by Trump in 2020. Evers sees the lame-duck session as a precursor to January 6 and says “there hasn’t been a peaceful transition of power” in Wisconsin since 2018.

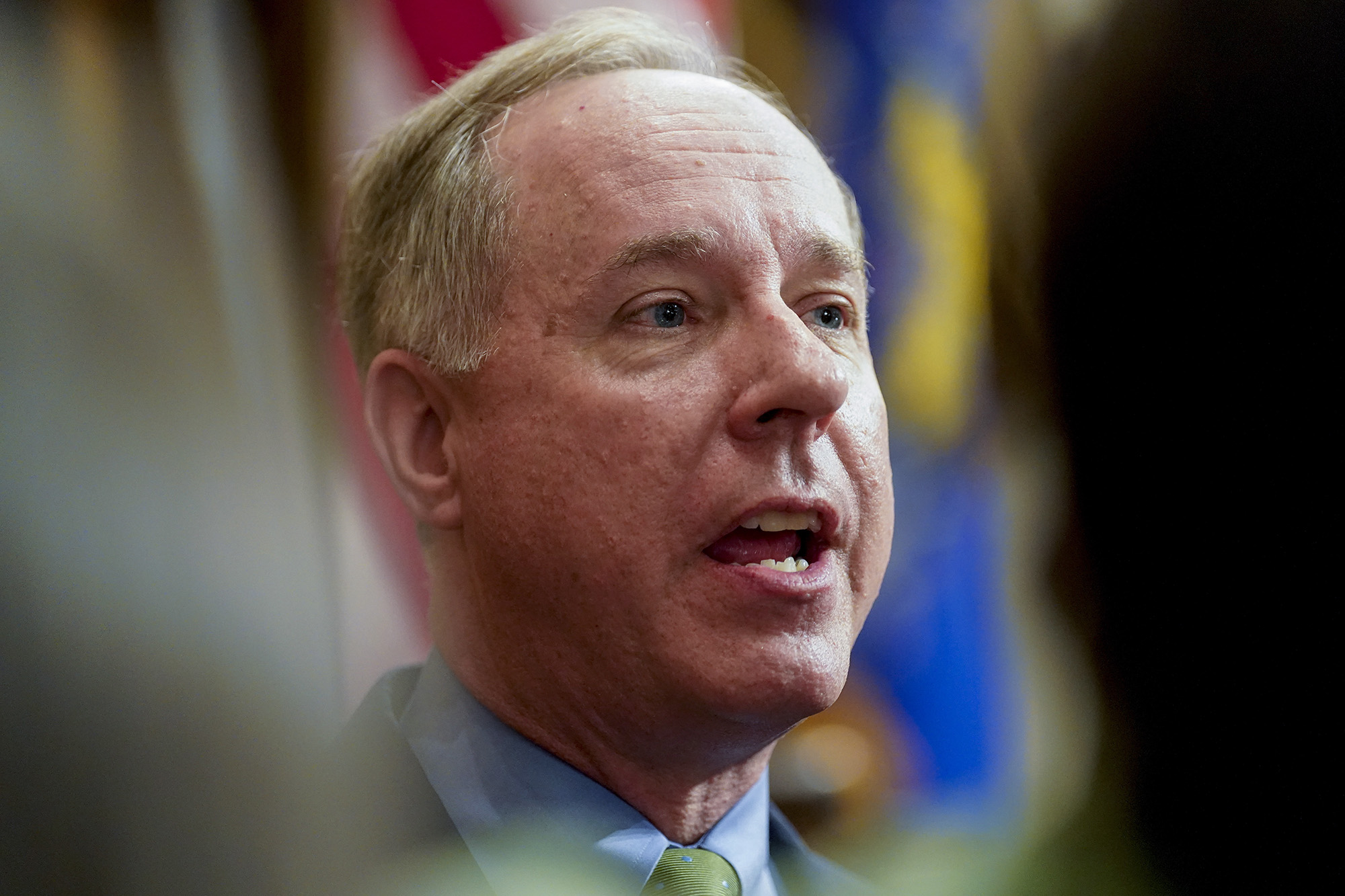

Wisconsin Assembly Speaker Robin Vos after Gov. Tony Evers addressed a joint session of the Legislature in the Assembly chambers in February 2022. On April 15, 2022, the Wisconsin Supreme Court adopted Republican-drawn maps for the state Legislature, after initially approving maps drawn by Democratic Wisconsin Gov. Tony Evers. Vos tweeted praise for the ruling, saying Republicans “have thought our maps were the best option from the beginning.”

Andy Manis/AP

“It’s the same deal, except they were successful in Wisconsin,” he told me. “They weren’t successful in Washington, DC. There are things that have never happened before in the state of Wisconsin because of that lame duck session.”

Polls found that Wisconsin voters opposed the lame-duck session by a nearly 2 to 1 margin. Though Democrats had won more votes and had public opinion on their side, Republicans claimed that only they could legitimately govern. “If you took Madison and Milwaukee out of the state election formula,” Vos said of the state’s two largest and most Democratic cities, home to 850,000 people, “we would have a clear majority.” The legislature, he claimed, was “the most representative branch of government and the closest to the people of Wisconsin.”

Four years later, the Supreme Court’s conservative majority employed a similar argument in its decision repealing Roe v. Wade, with Justice Samuel Alito writing that it was time to “return the issue of abortion to the people’s elected representatives.”

But Wisconsin has become a case study for how disconnected “the people’s elected representatives” are from the people themselves. Following the leak of the Dobbs decision, Evers called a special session of the legislature to urge the repeal of a deeply unpopular 1849 state law— passed by an all-male legislature one year after Wisconsin became a state and 71 years before women had the right to vote—that criminalized abortions, even in cases of rape or incest, and which would immediately go into effect if Roe was struck down.

The legislature is compelled to meet when the governor calls a special session, but not to act. And that’s exactly what happened. On June 22, two days before the Dobbs ruling, Senate President Chris Kapenga gaveled in and out in 14 seconds and walked off the floor as a Democratic senator yelled “objection!” About ninety minutes later, as protestors in pink Planned Parenthood shirts lined the Capitol rotunda holding signs with slogans like “The GOP Wants To Party Like It’s 1849,” Republicans in the lower house gaveled in and out in 25 seconds.

On September 21, Evers called another special session, asking legislators to authorize a constitutional amendment that would give voters the chance to repeal the abortion ban through a ballot referendum. He noted the law’s unpopularity: 61 percent of Wisconsin voters opposed the Dobbs decision, according to a Marquette University Law School poll, and 83 percent believed abortion should be allowed in cases of rape or incest. “When it comes to reproductive freedom, the will of the people isn’t the law of the land,” Evers said angrily, pointing to a phrase inscribed on the ceiling of the room where he signs bills and makes announcements. “But it damn well should be.” Once again Republicans gaveled in and out in seconds.

The legislature has routinely rebuffed Evers’ calls for action on popular policies like expanding Medicaid and strengthening background checks for guns, measures that are supported by 70 to 80 percent of Wisconsinites respectively. But the fall of Roe, more than any other issue, has illustrated to voters the real-world consequences of extreme gerrymandering.

“Thus far, we have seen Republicans make no effort to discuss or consider overturning the abortion ban or even modifying it,” says Neubauer, the assembly minority leader. “This is not what would happen if we had a fair map. Because Republicans would know that they couldn’t get away with holding this position.”

The GOP’s steadfast support for the abortion ban could very well cost Republican candidates in Wisconsin votes in close races this year, but Republicans in the legislature worry far more about primary challenges from the right than a general election defeat because of the deep red districts they represent due to gerrymandering. In an assembly with 99 members, only six races are truly competitive, according to Marquette’s Johnson.

Dale Schultz, who served as a Republican in the state senate from 1991 to 2015, including as majority leader, describes himself as pro-life but says he’s shocked that Republicans won’t even consider softening the 1849 law. “What that says to me,” he says, “is that democracy is dying.”

At the state GOP convention in May, held at a Marriott in suburban Madison, Vos candidly laid out his plan for total domination of state politics. His top priority, he said, was defeating Evers. But short of that, “we need five more people in the state assembly to make Tony Evers irrelevant,” he said.

The path to a GOP legislative supermajority runs straight through Wauwatosa, a charming city of 48,000 lined with 1920s craftsman bungalows and tall crab apple trees, that’s a 10-minute drive to downtown Milwaukee. It’s the kind of place where students walk to school and in the winter “you sled your kids to get a donut on Saturday morning,” says Democratic state Rep. Robyn Vining of her hometown.

On a sunny Tuesday in September, Vining gestures to a Catholic church on a hill in the city’s downtown, as its bells sound at noon. It lies within her district. She points out a coffee shop, chocolate shop, and craft brewery on the other side of the street. That is now in another assembly district. It’s all part of the same small, walkable neighborhood, but Republicans have quite literally divided her city down the middle. “It’s classic gerrymandering,” she says.

State Representative Robyn Vining goes door-to-door in her district handing out flyers for the upcoming elections.

Lianne Milton

Vining, an energetic 45-year-old photographer and former youth pastor, wore a blue t-shirt with hearts drawn by kids in her district that formed the shape of Wisconsin and seemingly knew everyone in the neighborhood. She represents the assembly seat formerly held by Walker before he became governor. Back when Walker represented the area in the 1990s, it was staunchly conservative: no Democrat had represented the city in the legislature for 60 years. Milwaukee is where 70 percent of the state’s Black population lives, but its suburbs are notoriously segregated and Wauwatosa has a troubling racial history. It was red-lined to dissuade Blacks from buying homes there. Up until the 1950s, signs posted on the city limits boasted of its “restrictive zoning.”

Though still more than 80 percent white, the city’s political sensibilities began changing during the Walker years. Vining, the daughter of a public school teacher, became politically active after Walker unveiled Act 10 in 2011. She took her kids, then 7 and 5, to Madison for their first protest, marching around the capitol with tens of thousands of other demonstrators during the frigid winter.

Three days after the 2016 election, Vining turned 40, celebrating her birthday by crying with friends in the back of a local wine bar and decided to run for the legislature, part of a wave of suburban women angered by Trump who would transform American politics.

Vining won by 138 votes in 2018, out of 34,000 cast, as the area became younger and more diverse. “We found a crack in the gerrymander,” she says. Republicans thought her victory was a fluke. Vos called her a “one-termer” and forbade Republicans from co-sponsoring bills with her. But in 2020, Vining was re-elected by 8 points and Joe Biden carried Wauwatosa by 34 points, a stunning shift in a city that voted for George W. Bush by 16 points in 2000. Another Democrat, Sara Rodriguez, flipped an assembly district that adjoined Vining’s district and also included parts of Wauwatosa by 735 votes.

Democratic campaign signs in Wauwatosa.

Lianne Milton

Republicans responded a year later by sealing the crack in the gerrymander, splitting the city into four assembly districts and three senate districts to dilute Democratic voting power. They packed Democrats into Vining’s district—essentially acknowledging they could not defeat her—in order to make the surrounding suburban districts, including Rodriguez’s, more Republican in their quest for a supermajority.

Despite Wisconsin’s history of competitive statewide and federal elections—Trump and Biden both won the state by roughly 20,000 votes—Democrats have flipped only three assembly seats in the past decade. All were in suburban Milwaukee. Under the maps drawn by the GOP in 2021, the number of districts outside Milwaukee where Republicans have a double-digit advantage has increased from four to seven.

Vining’s district, previously a rectangle stretching from more conservative Waukesha County to more liberal areas closer to Milwaukee, now zigzags north and south through the Milwaukee suburbs like a limp noodle. “It looks like something only a ninja could traverse,” she says.

Some graphics of the newly partisan-gerrymandered Senate District 5 and Assembly District 14, and what had happened on these maps to the cities of Wauwatosa and West Allis. 1/3 pic.twitter.com/KmE4taOlud

— Representative Robyn Vining (@RepRobynVining) April 19, 2022

Instead of being happy that she now has a safer district, she’s furious that Republicans “are trying to dilute the voices of suburban women” that helped Evers and Biden win the state. “Shouldn’t I care more about our democracy and our people than whether or not I have a job?”

The legislature can’t control state politics on its own, nor can it gerrymander every office. But by systemically limiting the influence of Democratic constituencies, GOP legislators have not only enhanced their own power but made it easier for Republicans to win control of other offices—most notably, the state Supreme Court, which has upheld nearly every move by the legislature to entrench its power. “Republicans have created this kind of self-perpetuating machine that is voter proof,” says Wikler. “It creates a world where there’s essentially no accountability to the vast majority of voters in our state.”

The story of how Republicans managed to ram through new redistricting maps over Evers’ veto provides a perfect illustration of Wikler’s point. In September 2021, Republicans approved a resolution outlining the principles they would use in drawing new districts for the next decade. Though they had moved 2.4 million people into new assembly districts in 2011 to create a firm GOP advantage, Republicans said the core aim of the new maps would be to “retain as much as possible the core of existing districts,” as if these heavily gerrymandered districts had existed for decades. (The 2011 maps were repeatedly challenged in court but ultimately upheld when the five conservatives on the Supreme Court controversially ruled in 2019 that partisan gerrymandering claims could not be brought in federal court.) This would be a shrewd way to preserve the GOP’s huge majorities while giving the new maps the veneer of legitimacy.

Around the same time, a conservative legal organization, the Wisconsin Institute for Law and Liberty (WILL), which has regularly provided legal ammo for the legislature in its disputes with Evers, filed a lawsuit asking the Wisconsin Supreme Court to draw new maps if the governor and legislature could not agree and apply “the principle of making the least number of changes to the existing maps.”

Image showing new redistricting line dividing N. 75th Street.

Lianne Milton

The house on the right is in State Rep. Robyn Vining’s 14th district.

Lianne Milton

WILL’s president, Rick Esenberg, told me he brought the case “as a matter of federalism” and said drawing new districts based on the 2011 maps was “the most neutral way to do it.” Esenberg dismissed claims that the new maps were “somehow illegitimate” and said that if Democrats wanted to win a majority in the legislature “all they need to do is learn how to talk to people in Fond du Lac [and] Oshkosh,” referring to two small cities in rural Wisconsin counties carried by Trump.

WILL was founded at the beginning of the Walker era in 2011 with start-up money from the Bradley Foundation—a hugely influential but little-known conservative foundation based in Milwaukee—to be “the ACLU of Wisconsin’s Right.” It was part of a sprawling network of Bradley-funded think tanks, media organizations, and advocacy groups that boosted many of the policy ideas behind Walker’s conservative agenda and pushed Wisconsin far to the right. More recently, the foundation has bankrolled groups instrumental in pushing Trump’s Big Lie; its board secretary, Cleta Mitchell, helped oversee Trump’s legal efforts to overturn the 2020 election and participated in the phone call where Trump asked Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger to “find 11,780 votes” to overturn Biden’s victory.

In the past, when the governor and legislature could not agree on redistricting maps, the federal courts stepped in to draw them, producing a fair compromise. Democrats believed that the same thing would happen in 2021. But in a surprise ruling in November 2021, the Wisconsin Supreme Court, with a four to three conservative majority, said it would oversee the redistricting process and would choose the map that made the “least changes” from the 2011 map—just as the legislature and WILL had wanted. Justice Rebecca Dallet, in a sharply worded dissent, wrote that the court’s decision to choose “2011’s ‘sharply partisan’ maps as the template for its ‘least-change’ approach” would have “potentially devastating consequences for representative government in Wisconsin.”

Although the decision practically guaranteed that the maps chosen by the court would be heavily stacked in the GOP’s favor, Evers produced a version that had more competitive districts than the legislature’s plan—giving Democrats more opportunities to pick up seats in areas like suburban Milwaukee—and hewed closer to the “least change” formula. On March 3, conservative swing justice Brian Hagedorn sided with the three liberal justices and chose Evers’ plan, which he said was “vastly superior” to the legislature’s proposal. It was a modest but important win for Democrats.

New redistricting lines has divided Harwood Ave, the historic center of Wauwatosa.

Lianne Milton

Within days, WILL and Republicans in the legislature shifted tactics and appealed to the US Supreme Court. As Milwaukee became more racially diverse over the past decade, Evers’ plan increased the number of majority-black districts in the city from six to seven. (The legislature’s plan cut the number of Black districts to five.) WILL called it a “21st-century racial gerrymander,” and urged the US Supreme Court to overrule the Wisconsin Supreme Court, saying the map violated the Voting Rights Act.

Voting rights experts viewed the appeal as a Hail Mary. The Supreme Court had routinely deferred to the states on such issues, expressly stating in 2019 that state courts had exclusive jurisdiction over partisan gerrymandering cases. And the court had repeatedly said states should not change voting laws or electoral boundaries laws close to an election; the filing period for candidates to appear on the August primary ballot in Wisconsin was only a month away.

Nonetheless, three weeks later the court’s conservative majority pushed aside these precedents and overruled the Wisconsin Supreme Court, accusing Evers of “embracing just the sort of uncritical majority-minority district maximization that we have expressly rejected.”

On April 15 (Good Friday)—which also happened to be the first day that candidates could gather signatures to appear on the August primary ballot—Hagedorn joined the conservative majority to choose the legislature’s map, which he called the only “remaining option.”

Sachin Chheda, director of the Fair Elections Project, which advocates for nonpartisan redistricting, compared the case to Bush v. Gore. “What we saw, at both the state and federal court,” he says, “was unprecedented intervention by partisan courts.”

In the 13th assembly district encompassing part of Wauwatosa, Sara Rodriguez had decided to run for lieutenant governor in 2022, so a volunteer on her campaign, Sarah Harrison, launched a campaign to replace her. Initially, she had assumed she would be running in the swing district that was preserved in Evers’ plan. But under the legislature’s maps chosen by the state supreme court, Republicans had cut almost all of Wauwatosa out of her district and shifted it 16 points to the right.

Harrison, who works in logistics, plays in an alt-rock band with her two sons, and referees roller derby tournaments in her free time, thought about not running. “Honestly, I was so angry about it that I said, ‘I can’t turn my back on it now,’” she told me at her home in Brookfield, 10 miles west of Wauwatosa. “Because I do not want the folks who cheated at the game to win.” Brookfield, though slowly becoming more Democratic, is still reliably Republican, filled with large McMansions and upscale malls. Harrison votes at a mega-church. Her neighbor flew a Trump flag “well after the election,” she said and on Biden’s Inauguration Day hung a yellow “Don’t Tread On Me” flag upside down. He now has signs for Michels and GOP Senator Ron Johnson hanging from the fence of his tennis court.

Her Republican opponent, Tom Michalski, a Waukesha County supervisor, is favored in the race, despite holding few campaign events and having only 33 followers on his campaign’s Facebook page. He says his top priority is “election integrity,” which has become the buzzword of choice for Republicans who want to signal their doubts about the legitimacy of the 2020 election without quite endorsing full-scale conspiracy theories. “I have no proof of fraud and I am not claiming fraud has occurred,” Michalski states on his website. “In response to COVID, election rules were relaxed, creating situations where undetected fraud could have occurred.” Citing “the lack of confidence that the election was conducted fairly,” he says that “changes in election law are a necessity.” (Michalski declined an interview request.)

Extreme gerrymandering in Wisconsin has reinforced the spread of Trump’s Big Lie among Republicans. Vos has said the legislature is unable to overturn the election results but has sought to placate Trump in nearly every other way. He named Janel Brandtjen, one of 15 legislative Republicans from Wisconsin who wrote to Vice President Mike Pence a day before the January 6 insurrection and urged him not to certify the 2020 electoral votes, as chair of the assembly’s election committee. In June 2021, as he faced a resolution at the state GOP convention calling for his resignation because he was not sufficiently supportive of “a real election investigation and a forensic audit,” Vos hired former conservative Wisconsin Supreme Court Justice Michael Gableman to lead a sprawling review of the 2020 election.

Former Wisconsin Supreme Court Justice Michael Gableman leaves the stand after testifying on June 23, 2022, at the Dane County Courthouse in Madison.

Kayla Wolf/Wisconsin State Journal/AP

Gableman was hardly an unbiased observer. The former justice appeared at a pro-Trump rally after the election in November 2020, telling a Milwaukee crowd: “Our elected leaders—your elected leaders—have allowed unelected bureaucrats at the Wisconsin Elections Commission to steal our vote.”

Over the course of his 14-month probe, he threatened to jail the Democratic mayors of Green Bay and Madison for not responding to subpoenas, called for dismantling the Wisconsin Elections Commission, and was held in contempt of court for withholding records from his investigation after a progressive watchdog group sued.

In March 2021, Gableman appeared before Brandtjen’s committee with an interim report and said, “I believe the legislature ought to take a very hard look at the option of decertification,” even though he left that conclusion out of the draft report he gave to Vos and later told the speaker that decertification was a “practical impossibility.” He also told the legislature that in future elections “the thumb should be on the scale in favor of withholding certification of electors.”

Two weeks after Gableman’s testimony, Vos met with John Eastman, the conservative lawyer who spearheaded Trump’s effort to persuade Pence to object to Congress’ certification of the Electoral College votes and is now a central figure in federal and state investigations into Trump’s attempt to overthrow the election. Although Vos had conceded after the election that Biden had won, he left the meeting with Eastman alleging there had been “widespread fraud.”

A recount requested by Trump and multiple independent investigations, including a legislative-ordered audit, has uncovered no such thing. An extensive report by WILL, though critical of aspects of how the election was administered, found “no evidence of widespread voter fraud.”

“Our report does not support the whole ‘Stop the Steal’ narrative,” WILL’s Esenberg told me. “I really think Republicans need to end their obsession with that.”

After paying him more than $1 million in taxpayer money, Vos finally fired Gableman in August, calling him “an embarrassment to the state,” but only after Gableman endorsed Vos’ far-right primary opponent, who came within 260 votes of ousting the powerful assembly speaker.

The damage has already been done. The lies spread by Trump and his allies have made voting harder in Wisconsin in tangible ways. In July, the Wisconsin Supreme Court outlawed most ballot drop boxes after WILL filed suit, arguing they were not authorized under state law. In September, another decision by a conservative judge in Waukesha County prevented election officials from correcting small errors on absentee ballot certificates, such as a missing zip code, which could lead to more ballots being thrown out in 2022.

After routinely ranking near the top of the country in voter turnout since the 1970s, Wisconsin has seen a dramatic decrease in voter access over the past decade. Republicans passed at least 33 different election changes during the Walker era, including a strict voter ID law that played a key role in Trump’s 2016 victory by suppressing Democratic turnout, particularly in heavily Black precincts of Milwaukee. One study by the University of Wisconsin-Madison found that the law kept up to 23,000 people from voting—larger than Trump’s margin of victory—in the two counties home to Madison and Milwaukee, with Black voters three times as likely as white voters to say they were deterred from voting. Another recent national study found that Wisconsin ranked 47th in the nation in ease of voting.

State Representative Robyn Vining goes door-to-door in her district.

Lianne Milton

The legislature wants to go further and has passed a series of bills this year, vetoed by Evers, that would make it more difficult to return mail ballots, tighten voter ID requirements, ban private grants to election offices, and, most ominously, give the legislature more power over how elections are administered.

After a campaign-finance scandal in both parties, in 2007 the legislature created a panel of retired judges—known as the Government Accountability Board—to oversee state campaign-finance laws and elections. It was well respected, but the legislature disbanded the board in 2015 after it investigated Walker for allegedly illegally coordinating with conservative dark money groups. The legislature replaced it with the Wisconsin Elections Commission, which was modeled after the Federal Election Commission, with an equal number of Democratic and Republican appointees and nonpartisan staff. It too was highly regarded—until Trump blamed the commission for his defeat.

Now leading Republicans want to dismantle the WEC, with Ron Johnson urging the legislature to “reclaim [its] authority over our election system.” In Wisconsin, presidential elections are certified by the governor while the commission chair certifies non-presidential elections. If Republicans retake control of the state in 2022, Evers says, “I think they’ll probably pass it off to the legislature and that will give them essentially carte blanche to muck up an election. For example, a presidential election.”

One of several water towers in Wauwatosa.

Lianne Milton

In Moore v. Harper, a case that will be heard by the US Supreme Court in December, Republicans will argue that state legislatures should have exclusive power over voting rules. Such a ruling would eviscerate checks and balances in places like Wisconsin and have enormous ramifications for the next presidential election, since Republicans control the legislatures in states comprising 300 electoral votes, including the six closest swing states in 2020. “It creates a fundamental risk to the popular vote within states,” says Daniel Squadron, co-founder of the States Project, which works to elect Democratic state legislative candidates.

Given these metastasizing threats to democracy, the stakes of the 2022 election in Wisconsin go much deeper than a partisan skirmish between Democrats and Republicans. The outcome could well determine the future of free and fair elections in the state—and in the country as a whole.

“It feels like democracy is on the ballot this November,” says Vining, “and it’s going to take everything we have in us to fight for it.”