The Greatness of ‘Norco’ Is Found in the Tenacious Weirdos Who Live There

One of the most troubling things that science fiction allows us to do is just to imagine that things go on as they are. The world doesn’t get much better or much worse, and instead things keep piling up and interacting until the shape of things is so garbled that an interesting story might emerge from it. For this reason, Norco is one of the best science fiction games ever made, being that it takes us into a future Louisiana with robots, alien specimens, and cults while holding onto the petrocultures, structures of violence, and the relationships with the land that echo across that region and the broader South. It’s a triumph of dystopia. I think it might be the future of video games.

I’m not trying to overstate it, but the past several years have seen some significant moves in the aspirations of video game storytelling. While there have been games “saying something” since the birth of the medium, the release of Disco Elysium in 2019 and the completion of Kentucky Route Zero in 2020 were a 1-2 punch of using familiar mechanics and ideas in drastically unfamiliar ways. In conversation with literature and film as much as other games, these story- and character-driven experiences put affects and feelings in the front seat. They were by no means singular, being in a cohort of recent games like Tacoma, Everybody’s Gone To The Rapture, Night in the Woods, Haven, In Other Waters, The Beginner’s Guide, and a handful of others that pushed game narrative beyond its usual scope and concerns.

These two games made a splash of significance that is difficult to understate, though, and that was partially because of the way that they provided portholes into their respective worlds. KRZ took players down a troubled path of history and discovery, tying up the personal with the regional with the universal, taking players through a rumbling set of emotional payoffs that gave me the same feeling as when static leaves through your fingertips. Disco Elysium brought us all to a decaying man in a decaying part of the world and gave us a direct injection of industrial-strength melancholy for the world that was and the world that could have been. And then, miraculously, it managed to give some glimmers of hope amidst all of that in a way that I had never really felt a game do before.

I have to talk about all of these other things before talking about Norco because I have the distinct feeling that Norco wouldn’t be here without them, or that at least the pathways that Norco took to get to us would not have been quite so open without these predecessors showing the way. Winner of the Tribeca Games Award in 2021, Norco released with a lot of expectations around it, and I have to be honest that I was a little worried. Would a game that spoke so well to a film-centered festival culture, even with judges familiar with games, be something that matched up to its peers?

Norco manages it, and it does so by diving deep into its genre. It is an extremely science fictional game, one that satisfies and confounds expectations for the genre with a deftness that most practiced noveslists cannot manage. The basic gist is that you’re Kay, a young woman who has made her way around a war-torn United States in a time of catastrophe, who has finally come home to southern Louisiana after her mother, Catherine, has died. The story transforms from a traditional narrative about a youth returning to a mess, including looking for her brother, into a conspiratorial tale about oil companies, cults, and rockets to space built way out in the bayou.

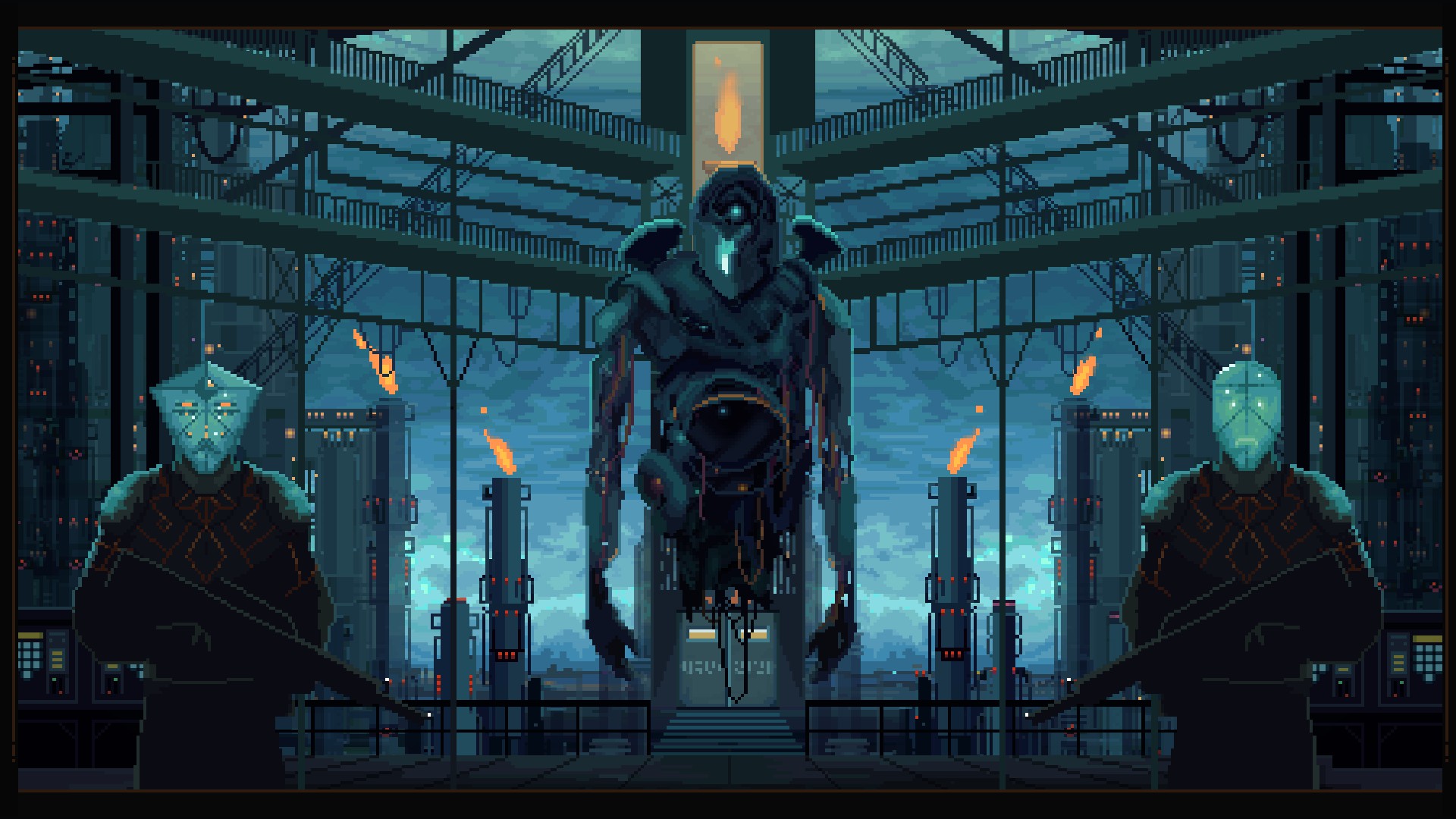

Norco’s world is an atrophied one, a place where the human spirit sticks its head out of the mud every now and again, but buries itself again when the vestiges of the state or corporate power start scanning the bayou for any signs of life to be expropriated. The heroes in this world, or at least the people who make moves that shake things up, are always unlikely. Kay partners up with robot with a constellation for a face and a secret in her heart that she can’t share; later, there’s a domestic terrorist named Lucky whose politics oscillate between righteous and childish. Private military guys processed through infinite corporate wars bump shoulders with drugged-out kids who just want to have a club night without the cops being called on them.

It’s a world that feels just as fucked up as the real one, and I have to stress that this matters a lot. The vast majority of the games I have played that science fictionally extrapolate our own world into slightly different conditions always want to pare it down. People become a “type of guy” and complex situations get turned into puzzles for clever protagonists to solve. There’s a general reduction principle at work here, as if to sell us on the strange world all of the thorns and burrs have to be stripped off.

Norco doesn’t do that. There’s a guy named Keith who wants to start a news website that’s called Keith’s Corner where it’s all about getting the news organizations and government officials “in the corner” in what can only be called a disastrously stupid metaphor. Keith is one of the most aimless, incompetent, and realistic characters I have had the luck of seeing in a video game. He lives and breathes. The profundity of him is entirely made up of how absolutely standard he is, as if he was stripped out of any bar where every hour is happy hour if you lean long enough.

One of the great accomplishments of both KRZ and Disco Elysium is that they gave us a sense of place and space. They made lived-in worlds where sad people tried to make do. Norco does that, and then it triples down on the people and how they make their lives in a place that is all but abandoned by anything that is not exploitative industrial capitalism. The point-and-click nature of the game, which switches back and forth between Kay’s adventure and a similar one her mother went on before her death, means that the vast majority of what we are actually doing in the game is talking with whoever is left in this little part of the world.

And they’re stuck there, really, either because of money or family or the tide of history. The people of this little bleak future don’t want to leave where they live, even though the land is poisoned to the extent of killing them and the opportunities to make life better are few and far between. Like in a Philip K. Dick novel, the people of Norco aren’t really phased by their condition because they’re all caught up in what they want to be doing in the short term. Some people are busy dying, others are looking for the bodies, and the vast majority of humans seem to just be searching for a way to make it to tomorrow.

The real turn here, what makes this dystopia so irregular and compelling, is that Norco is an elaboration on how this misfit cast of regionals finds meaning in connection with other humans. It is a game with society, and social pressures, so dense that you can barely breath in some places. The Garretts are the most direct evidence of this. They’re a cult of men who all dress like Best Buy employees and get the same haircut who are messianic leader who preys upon young, white, radically conservative men. There’s nothing here ripped from the headlines, and there’s also nothing here that rings false; it is all presented matter of factly, as if this is a logical conclusion of the slightly-more-future social media environment of this small pocket of the swampy south. Norco doesn’t flinch from this, in the same way that it flatly presents giant, mutant birds made up of alien machinery that have turned the bayous into networks via communicative tree roots. Anything added to the mix gets played out historically, as it might, with the people of this small world reacting as they might: wow, damn, some other shit to deal with.

The people who are displaced in floods find community; the unhoused find their people, even while abandoned by any system that might recognize them; the fishers in the bayou commune with the always-dead; Kay tries to build a family from dead mother, a father blown up by a corporation, a robot, and a brother who seems to recede with the horizon at every turn. Even Kay manages to staple it together. People find a way to keep living, and the most cartoonishly evil and foolish have a home they might enter into, and even one that might allow them to find some kind of grace. Or not. The private military companies are always here, after all.

The banality of the future in Norco is what allows all of this to sell and work well. Unraveling a weird conspiracy works when the gas station attendant is a machine and the local PI won’t tell you about the stuff a corp stole from your mother’s possessions until you buy him a second beer and some fries. The strangest curveballs make sense here, and these moments of utter plain future hellscape are punctuated by strange moments of beauty.

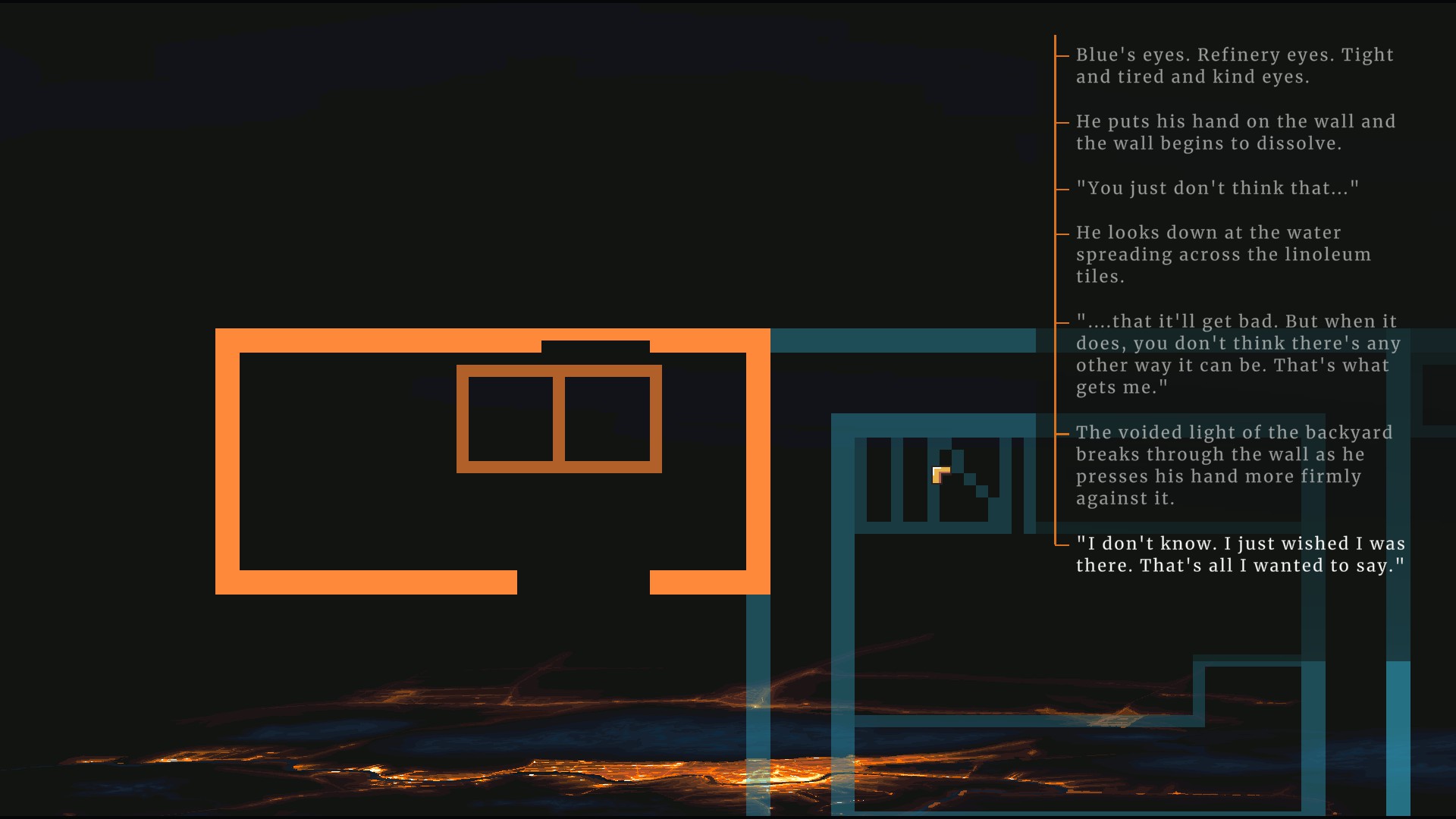

One of these sticks with me strongly. After fighting a psychic war against a number of enemies, I was presented with an architectural model of a house. Clicking the different rooms prompted Kay to experience a dreamspace echo of previous events and things that might have been; history and speculation bound up together. As I read these scenes, they slowly disintegrated, falling into a cosmic void where all of human thought ends up in the end. I walked through the house, room by room, as it disappeared. And then Kay woke up, with the end of the adventure still in front of her. That’s Norco.