The Moms Are All Right

Judging by its press since COVID began, you might think that married motherhood is a pathway to misery and immiseration. “Married heterosexual motherhood in America, especially in the past two years, is a game no one wins,” wrote Amy Shearn in one of many New York Times op-eds about the difficulties of marriage in the time of COVID. “Moms Are Not Okay: Pandemic Triples Anxiety and Depression Symptoms in New Mothers,” read a headline in Forbes. Bloomberg went so far as to suggest that family life was a financial dead end for women in an article headlined “Women Who Stay Single and Don’t Have Kids Are Getting Richer.”

The COVID-induced stresses of juggling work, child care, kids’ schooling, and lockdowns clearly made life difficult for many mothers, and navigating all of this with a spouse could bring its own challenges. “During the height of the pandemic, my mom-friend group chats roiled: I’m going to scream, typed women trying to do it all. I am seriously going to kill my husband and/or devour my young,” Shearn wrote. The New York Times parenting columnist Jessica Grose had a similarly dispiriting article, titled “America’s Mothers Are in Crisis,” pointing to a group of New Jersey mothers who had become so anxious during the pandemic that “they would gather in a park, at a safe social distance, and scream their lungs out.”

But was all of this negative commentary about marriage and motherhood, primarily written by and for left-leaning, affluent, educated mothers, an accurate reflection of reality? And today, as we put the worst of the pandemic behind us, are America’s moms still “screaming on the inside,” to borrow the title of Grose’s new book? Are they socially and emotionally worse off than women without kids?

Actually, no. As tough as motherhood was during COVID, mothers were both happier and more financially secure than childless women during the pandemic. This gap existed before COVID, but it continued during the worst days of the pandemic and has remained since then. This phenomenon is especially noteworthy because moms, and parents more generally, used to be less happy than childless adults as recently as the 2000s.

[Read: The pandemic exposed the inequality of American motherhood]

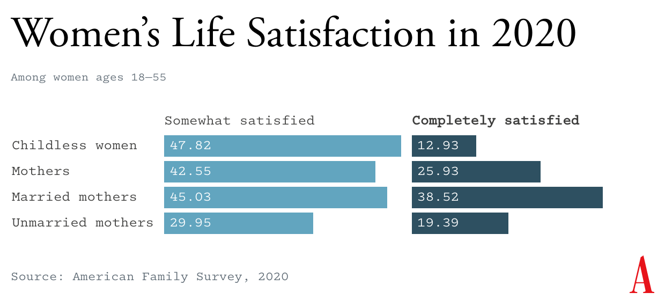

In 2020, 69 percent of mothers ages 18 to 55 were completely or somewhat satisfied with their life, compared with 61 percent of childless women the same age, according to our analysis of data from the YouGov/Deseret News American Family Survey, which annually surveys 3,000 Americans. It’s true that women saw their happiness dip from 2019 to 2020 as COVID set in, but this dip was more acute among childless women, according to the survey. Challenging as they were to care for while many schools were closed, kids seem to have brought a sense of direction, connection, and joy to the average mother’s life during the pandemic, at a time when so many other social ties were cut off.

Financially speaking, mothers ages 18 to 55 were also better off than childless women. The median family income for mothers with children under age 18 was $80,000 in 2021 but only $67,000 for childless women, according to the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey. These results are consistent with other recent research by the economists Angus Deaton and Arthur Stone, who found that American parents report more income and “daily joy” than their childless peers, even though they also report more stress.

The picture becomes more complex when we consider socioeconomic status. Poor mothers consistently report lower levels of satisfaction compared with wealthier mothers. This held true during the pandemic: In 2020, 62 percent of poor mothers were at least somewhat satisfied with their lives, compared with 79 percent of rich moms and 80 percent of middle-class moms, according to the American Family Survey data. This is perhaps not surprising given that lower-income moms were more likely than more affluent moms to lose their job and face child-care problems, as Stephanie Murray noted recently in The Atlantic.

However, wealthier moms experienced a COVID-induced decline in life satisfaction, while poor mothers stayed constant. The share of upper-income moms who reported being completely satisfied with their lives dropped a full 10 percentage points from 2019 to 2020, according to the American Family Survey. One possible explanation is that wealthier mothers were more likely to have had their life disrupted by social distancing—which was associated with emotional distress among mothers—compared with lower-income mothers.

Still, even in the worst moments of the pandemic, more prosperous moms fared better than poor moms. One explanation that many articles have overlooked is that wealthier mothers were more likely to have had a co-parent. A staggering 95 percent of rich moms had a husband or partner at home during the pandemic, as did 81 percent of middle-class moms. But only 55 percent of poor moms had a partner, according to the 2021 Current Population Survey. And despite all the media coverage discounting or minimizing the importance of marriage during COVID, mothers with partners were generally happier: In 2020, 75 percent of married mothers were somewhat or completely satisfied with their lives versus 58 percent of their unmarried peers.

Single parenthood has obvious financial implications, which helps explain why poor mothers are more likely to struggle to feed, clothe, educate, and house their children. And less money can translate into less happiness for parents. But there are also social and emotional consequences of single parenthood. In 2020, poor single mothers were the moms most likely to report loneliness—22 percent said they often felt isolated from others—whereas rich married mothers were the least likely to report loneliness: Only 2 percent said they often felt isolated, according to the American Family Survey. (Rich or middle-class unmarried mothers in the survey were too small a group to analyze.)

“Being a single parent is really lonely, even when you’re not social-distancing,” Shoshana Cherson, a 35-year-old single mother in New York City, told The New Yorker in the middle of the pandemic. “The whole support system I had put in place to keep me going has now completely fallen apart.” Another single mother in the city said: “Some days, I feel like I’m melting.”

[Annie Lowrey: The child tax credit was a little too subtle]

Even as we attempt to move past the pandemic, these trends are continuing to shape motherhood: The 2022 American Family Survey reported similar divides in loneliness and happiness along class and marital lines. This year, in spite of the challenges associated with parenting, affluent married mothers had a striking 30-percentage-point advantage in their reports of being somewhat or completely satisfied with their life, compared with poor single moms.

We have heard about these challenges and rewards in interviews. Lucy Fatula, a 37-year-old upper-middle-class mother who lives with her husband in Virginia, told us parenthood has entailed some sacrifice: “We gave up eating out whenever we wanted, hanging out with friends for” long stretches, and lots of sleep, she said. But it was worth it: “Seeing my sons happy gives me so much joy, especially knowing that I play such an important role in their lives.” Having a husband who is “a hands-on dad and is always supportive of me” has made the journey that much better, Fatula told us.

The tragedy is that millions of moms across the country, especially poor ones, are not similarly situated. Yet the roles of marital status and class have been strangely absent from our recent national conversation about motherhood. Maybe that’s because many of the dominant voices in that conversation have their own ambivalent or even negative feelings about marriage. What they don’t seem to appreciate is that their experiences are not representative of married motherhood in general, and that the hardship of navigating motherhood without a partner is especially great for poor mothers.

If the data tell us anything, it’s that, at least for most American women, the pathway to happiness runs through married motherhood, not away from it.