We’re All Capable of Going ‘Goblin Mode’

The people have spoken about what the people have spoken: The 2022 Oxford Word of the Year, chosen for the first time ever by public vote, went to goblin mode by a 93 percent majority. Oxford defines goblin mode as “a type of behavior which is unapologetically self-indulgent, lazy, slovenly, or greedy, typically in a way that rejects social norms or expectations.” It’s a gloriously evocative phrase—and it tells a concise story about how many of us are doing these days.

The first record of goblin mode occurred in 2009, when someone tweeted: “m was in full hyperactive goblin mode last night. it was as if she ate a bag of sugar-coated candy, then washed it down with a few red bulls.” Not much is known about m or the specifics of her behavior on that fateful night, but the description is vivid: Her primal side had been unleashed. Although the post received a lukewarm 22 likes, going goblin mode described a condition that, more than a decade later, has become all too familiar.

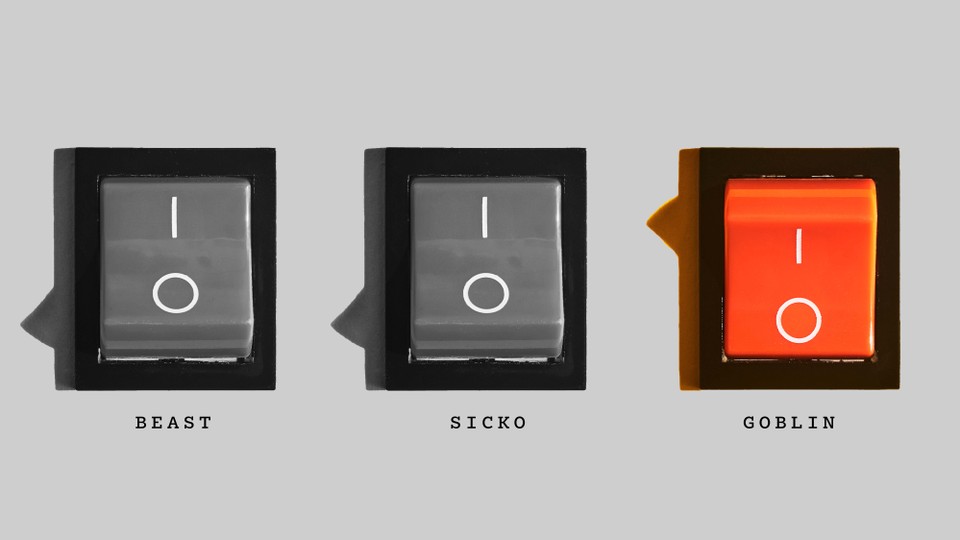

People have gone other modes before: We started to go beast mode, for example, in 2007, with savage mode and sicko mode following later. The metaphor originates in video games, where navigating a hidden challenge might activate another “mode”: a special style of gameplay where you might move 10 times faster or appear as a zombie. To “go X mode” is to summon the spirit of X for a stretch—going Caleb mode, for example, might mean overanalyzing internet slang.

Goblin mode returned with a vengeance in February 2022, in a tweet expressing mock disbelief at a Photoshopped headline: “Julia Fox opened up about her ‘difficult’ relationship with Kanye West,” it read. “‘He didn’t like when I went goblin mode.’” Fox, the actor/model who had just ended a high-profile fling with the artist now known as Ye, never actually used the phrase—but something about it resonated with the discourse of the moment. Fox’s eccentric style might seem goblinesque compared with the pristine InstaBeauty of the Kardashian empire from which Ye had been so recently banished. Goblin mode represented a full aesthetic rebound from immaculate self-presentation—perfect for a time when people were returning chaotically to public life from the madding bowels of pandemic isolation. “The term then rose in popularity over the months following,” Oxford University Press said, “as Covid lockdown restrictions eased in many countries and people ventured out of their homes more regularly.”

[Read: The year without germs changed kids]

Western mythology is littered with all sorts of goblins: shape-shifting animals; demonic, fairylike creatures; rude and hairy humanoids. What typically separates them from other supernatural forces is not their physical appearance but their passion for shelter. Goblins tend to lurk in cozy spaces. Most early accounts place goblins in caves; eventually, during the ascent of urban European life in the 15th and 16th centuries, stories described them as dwelling in houses.

Goblins represent the impish un-self-consciousness of our private lives. They’re ugly little monsters who love making mischief around the home. They have more fun than trolls because, instead of waiting under a bridge to hurt someone, they’re just chilling at the crib, looking nasty and getting up to no good. Maybe they haven’t showered in a few days, but they’re not evil. They just want to stay in and play. Sound like anyone you know?

In the early days of the pandemic, many of us unlocked a new mode in the video game of life: demonically uninhibited domesticity. Through countless quarantines, we all became “m”: pent-up balls of energy bouncing off the same four walls, maniacally scrounging up fun in confinement. Unable to party elsewhere, we transformed our home by necessity into a stage for chaos and revelry. I myself would not be writing complete sentences today had my housemates and I not developed a weekly ritual of getting blisteringly wine-drunk and screaming obscenities at the movie Cats.

[Read: Just embrace the madness of Cats]

The ability to go goblin mode was a necessary evolution, forged in trauma. But it now remains with us as a superpower. As we emerge from our caves after that long hibernation, our goblin-selves lurk somewhere deep inside us, beckoning us back home to vibe out. I don’t see going goblin mode as “self-indulgent, lazy, slovenly, or greedy” at all. It’s refreshingly authentic and deeply cathartic. In goblin mode, we can become our true wild selves, unkempt and offstage, triumphantly invisible to the public eye.

I might define goblin mode as “unbridled domestic liberation” or “a complete shedding of the mask of public life” or, my personal favorite, “staying home and getting weird.” Whatever you call it, I’m grateful for my newfound ability to go goblin mode. Now get out of my house so I can act unhinged.