Friday essay: grief and things of stone, wood and wool

Following the death of her elderly father, a close friend of mine recently asked if I would read a poem by Goethe at his funeral.

I didn’t know the man well. In fact, I had met him only once, seated in my friend’s car on a Fitzroy street on a sunny day several years ago. What struck me about him at the time was the mischievous smile he wore and the youthful sparkle in his eyes. I felt honoured to be invited to share in the celebration of his life.

Although my friend is near a generation younger than me, we are very close. I have known her since she was a shy but determined young person. She has since become an advocate for the rights of Indigenous people in Australia and the South Pacific. She is thoughtful and kind and fierce whenever the situation requires a “warrior woman”.

The funeral service took place at a community hall in the Dandenong Ranges, east of Melbourne. Family and friends of the man who had passed spoke, sang and prayed (in their own way) about the remarkable life of a person who had survived the ravages of war-torn Europe, the loss of loved ones, separation from family and an eventual migration to Australia, where he fell in love, raised a family and continued his lifelong passion for the natural world.

Before I left home for the funeral service, my wife, Sara, asked me, “Will you be okay?” My younger brother had died suddenly only weeks earlier, and I remained grief-stricken by the experience of finding him in the small government flat where he’d lived for two decades. I answered Sara’s question with a dismissive, “I’ll be fine”.

Of stone

And I was fine. Following the death of a person you love dearly, a person you yearn to see just once more, a person you want to say just one more goodbye to, isolation can become a tempting companion. You feel that nobody understands the depth of your grief.

Appointments, work, conversations with friends – they all make little sense. Mundane tasks become even more meaningless. My retreat into self-imposed isolation had become debilitating. Attending a funeral in the mountains was, if nothing else, an escape from my solitary confinement.

A few hours later I found myself in a room crackling with the energy of those who had gathered, along with the man who had bought us together for the day, who was resting in a wicker coffin at the front of the room. As I read the poem for him and his family, I thought again about my own brother and felt comforted, for the first time in weeks, that I was not alone. I was sharing a valued life among the living.

Following the burial at a local cemetery, we were invited back to the community hall, where we enjoyed food and stories about the life of my friend’s father. I noticed a wooden table where a range of items had been placed: books, hand tools, photographs and other secondhand objects you might find at a garage sale. My friend took me over to the table and explained that each of the items had belonged to her father and held particular significance for him and his family. I was invited to choose an object and take it home with me as an act of commemoration. I hesitated. It didn’t seem right that I should take something personal belonging to a man I’d hardly known.

My friend gently nudged me. “Go on, pick something,” she said.

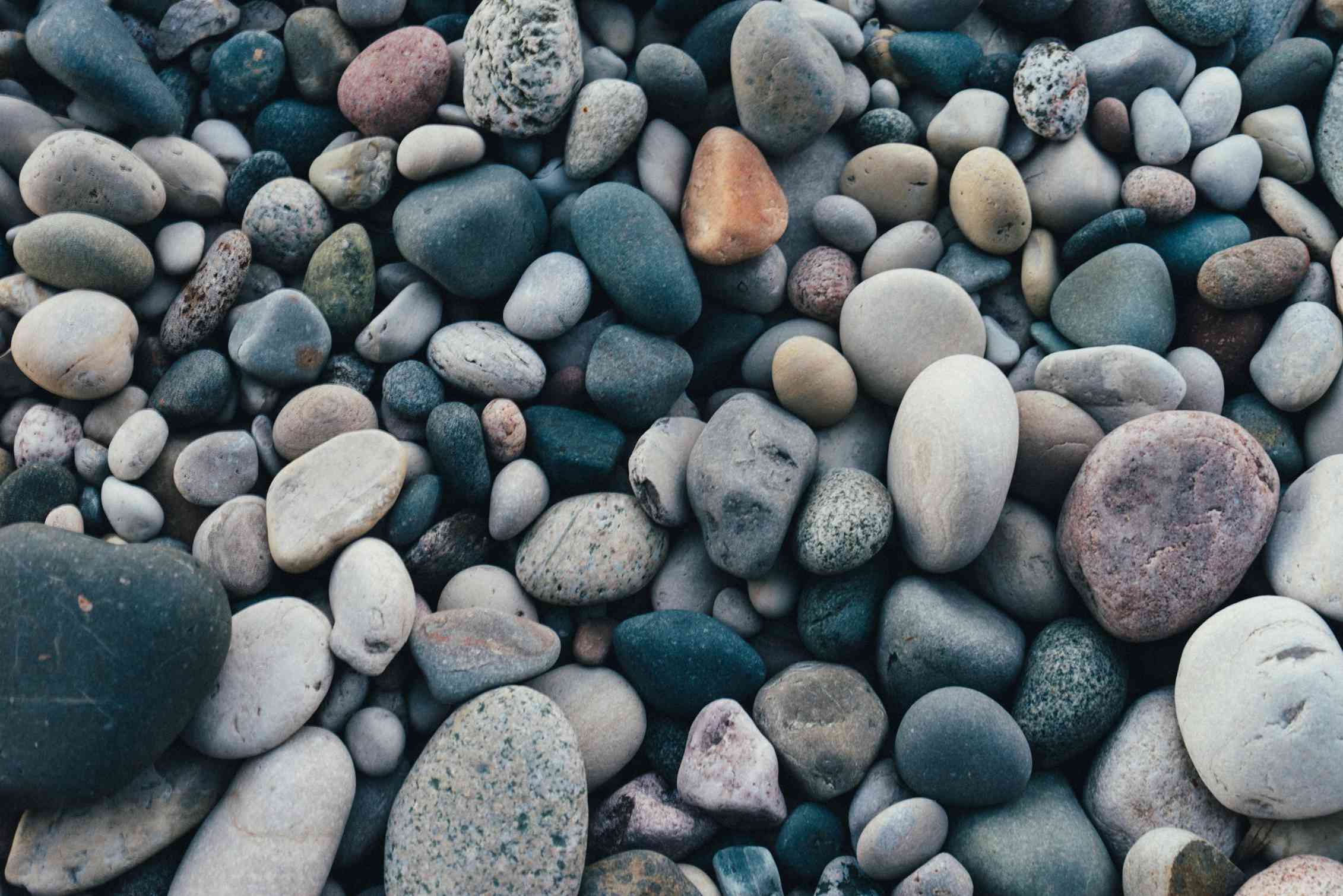

My eye was drawn to an egg-shaped, ivory-coloured stone, speckled with an earthy pigment. I picked up the stone. It sat full and heavy in the palm of my right hand. I turned it over. Its centre was smudged with a dark stain. It appeared that someone may have held the stone in their hand and rubbed it (and rubbed it) with the back of a thumb.

“Can I have this?” I asked my friend.

“Of course,” she answered. “It’s a good choice for you.”

The stone now sits on my writing desk. I often hold it in my hand when I’m thinking about the words I want to write (as I’m doing now). I have thought with the stone about life and death and my love for my friend, who misses her father so deeply. The stone has affected my thoughts on climate justice, which is a key area of my academic and community research.

What I have come to understand about the stone is that it is stronger than me – and you. It is also patient and thoughtful to an extent that human society appears to be incapable of. If we manage to destroy ourselves in the future, and destroy non-human species and vital ecological systems in the process, it will be because we don’t possess the humility and wisdom of the stone. Unfortunately, many in positions of power and influence appear most ill-equipped to recognise this. The stone has invited me to reflect on love, and on death, including my own. The stone also reminds me that seemingly inanimate and soulless objects have guided me throughout my life, particularly when I am reaching for understanding.

Foraging

If I wasn’t born to forage, I was taught to from a very young age. Growing up in the inner Melbourne suburb of Fitzroy in the early 1960s, we were very poor. (As poor as a Monty Python shoebox.) We were always a gleaning family, out of necessity. The open fire in our two-room terrace was fed with scraps of wood we gathered from the streets, empty houses and vacant blocks.

Coming home from school of an afternoon, if my older sister and I spotted an eight-foot long plank of wood, we’d pick it up, cart it home and add it to the woodpile in the yard. My brother and I collected scrap metal – lead, copper and brass – and sold it to a dealer who had a yard behind a pub on Brunswick Street.

I later came to cherish the narrative power of found objects through my grandmother, Alma, who introduced me to op shop fever, an ailment I continue to live with 60 years later. From the age of around four or five, hand-in-hand with my Nan, I’d walk from Fitzroy to the Salvation Army’s “Anchorage” in Abbotsford, around a mile and half in the imperial measurement of the time. The Salvos’ secondhand business could not be described as a “shop” or “store”, but a series of rusting corrugated-iron sheds on the bank of the Birrarung.

Each shed was dedicated to particular items: ornaments, household furniture, books and comics, and children’s clothing. Nan and I would move from shed to shed, with the rule that I could buy one book, one comic and one item of clothing. She liked to spend her time in the ornaments shed, searching for a vase, or a gravy dish perhaps, that she could add to the mirror-backed, glass-fronted cabinet in the front room of her Fitzroy house. Once an item went into the cabinet, it stayed there, never used and rarely touched – any item put into the cabinet was for “show”.

I loved my books and comics, but most of all I sought out a t-shirt or jumper, especially a warm woollen jumper, largely for practical purposes. Winters in our house and on our street were cold. A jumper provided warmth. A jumper purchased secondhand was my jumper, not one that had been handed down to me by my older brother. And when I put a thick woollen jumper over my head as a small child, my body felt protected, emotionally and physically. Woollen jumpers became my security blanket, and that desire for fabric has never left me.

I have a cupboard full of woollen jumpers at home. Some have been collected from the op shops I continue to visit each week. Others, bought new, are quite expensive. Any time I become particularly anxious, or feel the desire for “comfort clothes”, I put on one of my jumpers. (Summer is not my favourite season.) Recently, while experiencing a near emotional collapse, a crafted woollen object rescued me.

In Booktown

I was in a Victorian country town on an autumn morning as a guest of the Clunes Booktown Festival, which I’d been invited to some months previously. My younger brother had died a few weeks before the festival. I had begun to write about him, as it was my only means of understanding, if at all, what I was experiencing. I have since written about his death several times, with each essay building on the previous one, including conscious repetition (which I am doing now). The essays focus on walking country, travelling and remembering, with my brother at my side. Perhaps I am not repeating myself, but rather engaging in the act of reiteration as a means of paying my respect to his life?

Immediately after my brother’s death I cancelled several commitments, took weeks away from work and spent as much time as I could with my grieving mother. I had simply forgotten to cancel Clunes and felt obliged to attend when I was reminded about the festival only days before it was to begin. I drove there with Sara.

Clunes is a gold rush town in north-west Victoria and proudly carries the title of Booktown. On arrival, we parked the car alongside a bluestone church above the town. It was a cool and clear morning. Walking down the hill towards the festival, I suffered what I could only explain as an anxiety attack. I needed to sit down. I enjoy writing-and-reading festivals and I love the warmth of audiences. But, sitting on a bench in the main street of Clunes, I suddenly realised that I would be incapable of performing at all. I wanted to go home and hide. Sara suggested that a coffee might pick me up, although she was also ready to leave and drive me home if that was what I decided.

We went for a walk and I bought a café latte, an object of right-wing disdain. I took a sip and felt a little better. We spotted a craft stall selling woollen products: scarves, gloves and beanies. My eye was drawn to a naturally dyed beanie, chocolate and (sort of) aqua coloured, with a chocolate pompom on top. I picked the beanie up and held it in my hands. The wool was soft, the texture rich. With the permission of the woman standing behind the stall, I put the beanie on. It wrapped itself gently around my head. Feeling immediately comforted and secure, I smiled at Sara and said, “Let’s go.” We walked back up the hill, into the Clunes Town Hall, where we were met by a room crowded with generous people.

Gathering through the years

As we grow older, some of us begin to dispose of our possessions. Others continue to hoard. Thinking back to the table of objects at the funeral I attended, I experienced it as a generous and communal gesture, yet another act of reciprocity and energy.

My stone continues to teach me about the contrasts between humility and arrogance, between the world we are wilfully attacking and our self-destructive stupidity. The stone has also sharply focused my attention on the deep value of my relationships with other people. My friend who lost her father has been in a state of grief since his passing. When I hold the stone, or glance at it sitting on my desk, I think of my friend and I am reminded that she is in my care, as I am in hers. The thought strengthens me and gently reminds me to remain aware of my obligation to her. For this, I can thank the stone and the man who first picked it up and held it in his hand.

As I write this I am 62 years of age. (That’s old for an Aboriginal man!) I have five children, two grandchildren and a loving partner.

On July 4 1996, my grandmother, Alma, was in St Vincent’s Hospital in Fitzroy, dying of renal failure. Although I was a grown man, about to turn 40, I sat by the window of her room on the tenth floor, a child again, looking over the streets of our shared life. She passed away that night. My mother decided that our first task after her death was to empty out her Housing Commission flat and scrub it clean.

My grandmother’s flat was crowded with the objects she’d collected from op shops over 60 years. The family gathered at the door of my grandmother’s flat and my mother said, “Each of you pick something of love. The rest we pack up in boxes and drop at St Vincent de Paul’s in Collingwood”.

My initial thought was that it was reckless of my mother to sweep away Nan’s possessions so soon, and my older sister felt the same, whispering to me, “Shit. Nan’s not even cold yet”.

Our feelings shifted to acceptance, and subsequently deep satisfaction once each of us had chosen our love pieces. I picked a ceramic teapot mat, an ancient stone hot water bottle and a squat glass jar that my nan would fill with tomato sauce so that we could sit around her kitchen table and dip our hot chips into it.

A week later, I walked into the local op-shop and noticed a young woman pick up an orange flower vase that had belonged to my grandmother. She held it up admiringly. Light passed through the vase and the woman’s face glowed with happiness. She paid for the vase and took it home.

What’s left behind

When my brother died died last year, my two sisters performed the same ritual in his government flat. Whatever else might be said about a working-class Aboriginal-Irish family, we’re fucking spotlessly clean!

We took the goods we’d each decided to keep around the corner to my mother’s house. There were three guitars, two crucifixes and several books, including a copy of my short story collection Common People, which was sitting on the side table next to his bed on the morning I found him dead.

My sisters allowed me to take his acoustic guitar home as long as I promised that I would learn to play it. I walked home with the guitar under my arm, wondering what would happen to my own stuff when I died.

The books will continue to be treasured and read, I’m sure. I’m concerned for the bowls of collected pine cones scattered around the house.

My grandson, Archie, is 14 months old. Recently, I introduced him to the pine cones, naming them individually, hoping for attachment on his part. I took him on his first pine cone forage in Carlton Gardens. My motivation, of course, is that when I die and they come to sweep my life away, Archie will intervene, say, “Not so soon” and rescue my pine cones.

I don’t know what will happen to my woollen jumpers, scarves and beanies. If I was able to choreograph my own wake (as my mother has done in a lengthy list), or if this was a short story I was writing for you rather than nonfiction, I would die during a cold winter and my family would be gathered around a fire reminiscing about my life. My children, Erin, Siobhan, Drew, Grace and Nina, would each be wearing a “Tony Birch find” (as I refer to the jumpers); my grandkids, Isobel and Archie, would be each be wrapped in one of the many brightly coloured scarves I’ve collected; and Sara would be wearing the precious striped beanie that saved me on a beautiful morning in Clunes.

This is an edited extract republished with permission from GriffithReview68: Getting On (Text), ed Ashley Hay

Tony Birch does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.